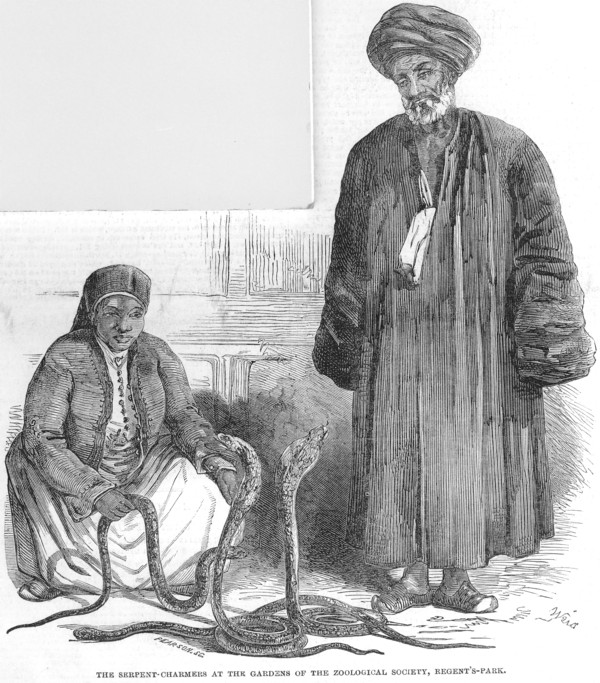

These remarkable persons, whom our artist had an opportunity of sketching at their first performance, state that they are of the tribe called Rufaiah, who hand down the mystery of serpent-charming from father to son, and whom the most venomous species have no power to injure.

Rufai, whom they regard as the founder of their craft, appears to have been a Mussulman saint. His tomb still exists in the neighbourhood of Busrah, and Is frequently visited by the Rafaiah desirous of paying honour to his memory. It is said to be infested by great numbers of serpents of various species; but they are strictly controlled by the spirit of Rufai, and are forbidden by him to injure the pilgrims, who enter freely and fearlessly among them.

Whatever amount of faith is to be attached to their legend, it is certain that the Rufaiah now in this country handle the Egyptian cobra-which they call tabais nouascher—in a manner which evinces their entire fearlessness of its bite. They irritate it, soothe it, receive its open-mouthed attack, or its gentle caress, as their own caprice or the request of the spectators may suggest.

The boy is the most active operator, and generally monopolises nearly the whole of the performance; the old man, Jabar Abou Haijab, occasionally supporting him. Jabar is held in Egypt to be the father of the profession: he acted as collector to the French savans in 1801, and has been conversant with snake-lore from his earliest youth.

After exhibiting three or four cobras together, in the erect and striking pose which is common to the Egyptian and to the Indian species, they generally conclude their performance by a feat, of which we are at present unable to suggest a solution. Catching up a serpent without any apparent premeditation, the boy opens its mouth, either spits or blows into it, and then throws it down apparently lifeless. As it falls, there it lies, dank and limp, until he chooses to take it up. After two or three passes through his fingers, It recovers its suspended vitality, and on being placed again on the ground, exhibits itself instantly in as rapid motion as if no interruption had occurred to it.

The practice of serpent-charming among the Arabs appears to differ essentially from that of the Hindoos. It is certainly as old as the time of Mohammed, and probably derives its origin from a period of the most remote antiquity.