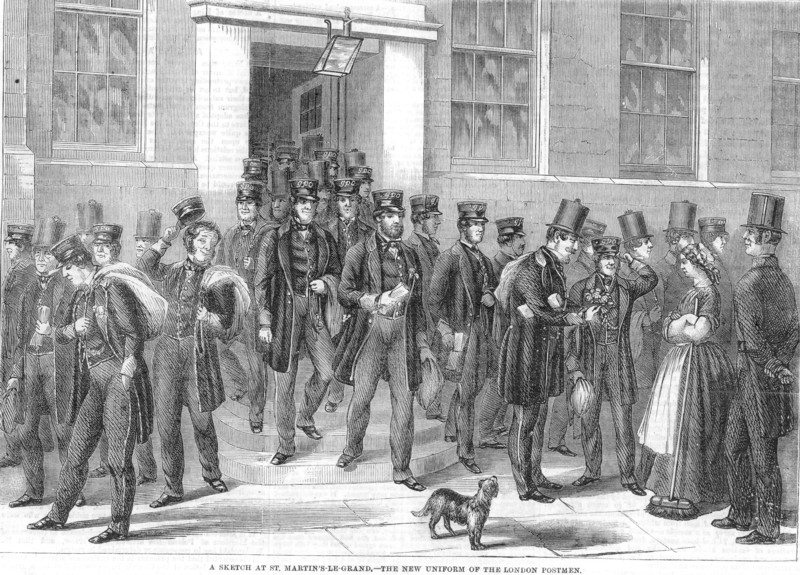

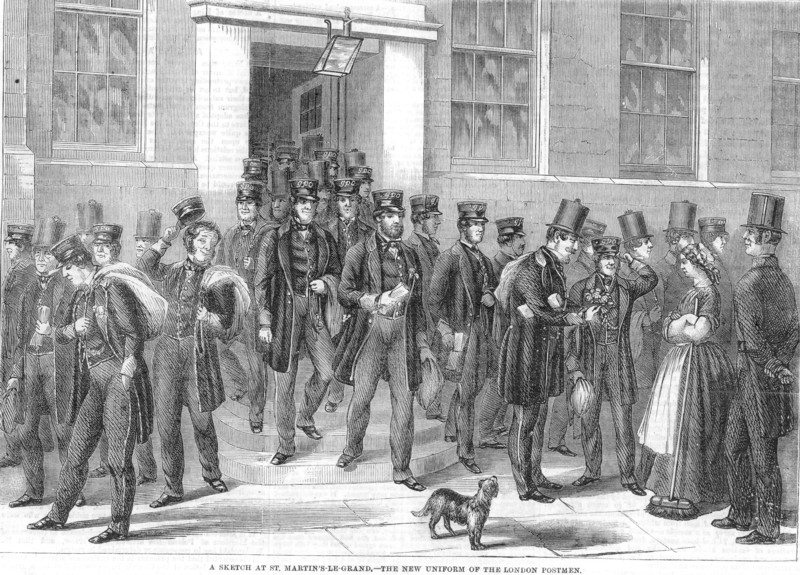

Source: The Illustrated London News, August 10, 1861

The old familiar scarlet tunic by which we were used to recognise the London General Postman has now become a thing of the past, having been superseded, on the 10th of last month, by a new uniform, which consists of a blue tunic, edged with scarlet, and with scarlet collar and cuffs; trousers of grey tweed, with a red cord stripe, and a peaked blue cap, with a black leather rim and a red edge at the top. The average weight of these caps appears to be about 9 oz, and, including the glazed cover, about 11 or 12 oz. Only a limited number of these caps have at present been issued, the contracts not yet being completed. The postmen's grievances have long been before the public; but it is satisfactory to report that they are now to receive two new dresses in the year, instead of one, as formerly.

One of the most prominent figures in the group of postmen shown in our Illustration is the individual known throughout the city by the cognomen of "the Emperor," and whose portrait will he readily recognised. He does not appear to have received his peaked cap with its distinguishig number, as he still wears one of those large and enormous1y-heavy hats which seem to have been manufactured especially for the unfortunate letter-carriers doomed to wear them all the long day. Rather a good story is current respecting Napoleon III's double. It seems that during the private sojourn of the Empress in London last winter she took particular interest in the Cattle Show. Certain waggish officials availing themselves of that fact induced the Emperor's duplicate to accompany them thither one evening. The conspirators having previously thrown out some serious hints as to the expected presence of the Emperor incog. the report spread like wildfire, and the mingled sensation of curiosity and awe created by his presence within the building was something ludicrous, particularly when taken in connection with the great embarrassment displayed by the unsuspecting duplicate at finding himself the object of so much attention. Fortunately for the Empress she was not present on the occasion.

In regard to the class of men from which the postmen are drawn the following may serve as a sample:—Of 255 candidates who were nominated in 1859, 71 had been porters, domestic servants, &c.; 85 operatives of various kinds, 52 clerks and shopmen, 22 farm-labourers and gardeners, 5 schoolmasters, 3 soldiers and sailors, and the remainder of no particular occupation.

The medical officer recommends that young men from the country accustomed to outdoor labour should generally be preferred to London shopboys, tradesmen's assistants, &c. The Postmaster General's report for the present year has net yet been issued, but according to the last return there were 11,363 letter-carriers, messengers, &c., in the United Kingdom; the entire postal staff of the department at home and abroad is returned at 24,802; the London district employs a staff of 3300, of whom about 1500 belong to the chief office at St. Martin's-le-Grand.

The wages of the London postmen commence at l8s. per week, and, if diligent and well-conducted, they receive an increase of 1s. per annum until they reach 25s., with the chance of promotion to be sorters, or even clerks. The promotion is said to be by merit; but one of the complaints of the men appears to be that merit means favouritism, or, as they term it, "toadyism." That is a point, however, on which an impartial opinion could not be expressed without a most elaborate investigation. The maximum amount of labour which they are supposed to perform is eight hours per day; but that does not include the time occupied at each delivery in going to the point where the delivery commences and returning from the point where it terminates to the office.

Every letter-carrier has in each year a fortnight's holiday, without any deduction from his income. He has also the benefit of gratuitous medical advice and medicine, and attendance at his own home, if he requires it. He is secured a pension in old age and is encouraged to make some provision for his family by a weekly contribution for the insurance of his life, the department paying 20 per cent of his annual premium. The principle is admirable, but it may be difficult for a poor man, with a family to support, to make any deduction from his wages. Another excellent institution is a mutual guarantee fund, by which the men are relieved from the necessity of providing personal securities.

The report states that "in the London office, where the plan has been in operation nearly two years, the sum already invested is upwards of £700, and the defaults have been so few and so small in amounts that there is reason to hope that the interest of the fund will more than cover the claims upon it, and that every officer on quitting the service will receive back more than the amount of his original deposit." In regard to the libraries—"At the chief office at St. Martin's-le.Grand, and at each of the London district offices, except the south western, a library, on a greater or smaller scale, and including generally some newspapers, has been established for the letter carriers, and in great part at their own cost." The fact that, in 1859, 545 millions of letters and 70 millions of newspapers were delivered in the United Kingdom may give some idea of the postmen's labours; the universal adoption of letter-boxes would afford great service not merely to the postmen, but to the public generally.

We hear much of the robberies committed by the letter-carriers, and there are, doubtless, many of which we never hear at all; but in such a large number of men there must be many rogues who would be robbers under any circumstances. The real cases rests with that careless portion of the public who recklessly send money and articles of value through the post, thus keeping the, demon Opportunity continually hovering round the nimble fingers of needy men. As a sample of public carelessness, more than 11,000 letters were posted in 1859 without any address at all. An enormous amount of trouble is also caused to the men by incorrect or indistinct addresses; from the same cause about 470 newspapers were undelivered, being 1 in 150 of the whole number. "The cause of non-delivery is sometimes carelessness in the folding, and the damp state, of the covers occasionally, when the papers are received from newspaper agents. But it is found that, however caused, in the London office only 1 newspaper in 5000 escapes from its cover."

But it is not merely to the dangers of temptation that the poor postmen are exposed, as appears by the periodical request of the Postmaster, that the public will not send through the post, leeches, knives and forks, gunpowder, and lucifer-matches—awkward companions, certainly.